Introduction

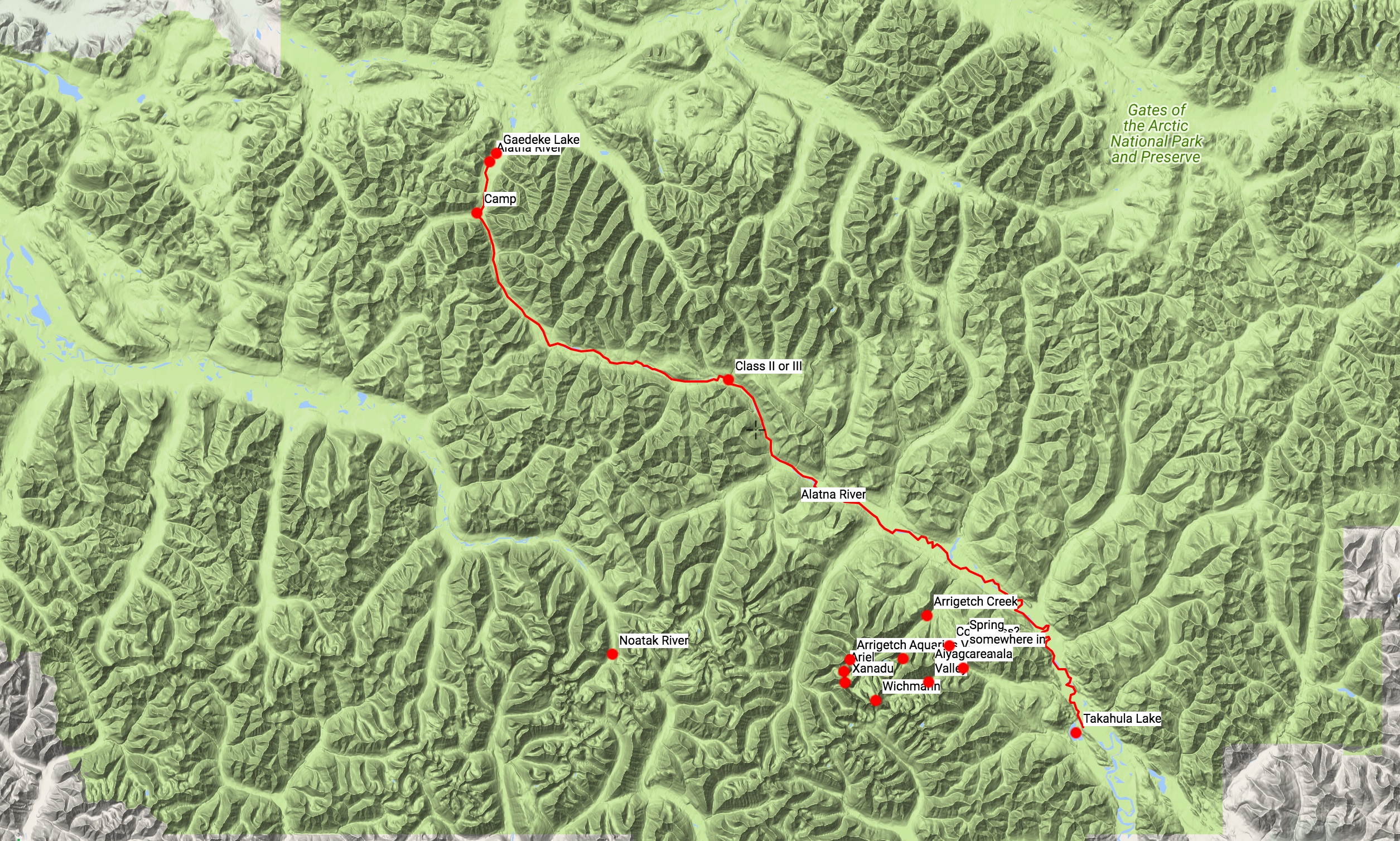

When I first saw the Brooks Range of northern Alaska on a map, I knew I had to see it in person. North of the Arctic Circle and running east to west, the range is 700 miles long and 150 miles wide…and to top it off, Gates of the Arctic National Park and Noatak National Preserve protect over 13 million (MILLION!) acres of contiguous, road-less wilderness. Without a doubt, this was the type of backcountry I wanted to experience. The vastness of the wilderness was almost incomprehensible and I wanted to disappear in its wide valleys. Gates of the Arctic has no official trails, no roads, and the only ways to get to it are by walking or flying from one of the few tiny villages that can be found on the outskirts of the range. It is a harsh environment with very short summers, 24-hour daylight, strong winds, unrelenting terrain, grizzly bears, wolves, hazardous rivers, and no help for as far as you can imagine. This is not a part of the world that can be taken lightly.

When I first saw the Brooks Range of northern Alaska on a map, I knew I had to see it in person. North of the Arctic Circle and running east to west, the range is 700 miles long and 150 miles wide…and to top it off, Gates of the Arctic National Park and Noatak National Preserve protect over 13 million (MILLION!) acres of contiguous, road-less wilderness. Without a doubt, this was the type of backcountry I wanted to experience. The vastness of the wilderness was almost incomprehensible and I wanted to disappear in its wide valleys. Gates of the Arctic has no official trails, no roads, and the only ways to get to it are by walking or flying from one of the few tiny villages that can be found on the outskirts of the range. It is a harsh environment with very short summers, 24-hour daylight, strong winds, unrelenting terrain, grizzly bears, wolves, hazardous rivers, and no help for as far as you can imagine. This is not a part of the world that can be taken lightly.

But I had to go. The vastness of the wilderness virtually demanded that I go see it.

The first obstacle when looking at a map of a mountain range with no trails and no road access is trying to decide where to go. As I researched the range, I found photographs of a set of granite spires that rose out of the alder covered valleys. The peaks were called the Arrigetch, which means “fingers of the outstretched hand” in Inupiat. And those fingers seemed to beckon to me…I had to see them. And as I looked more closely at the area around the Arrigetch, I noticed a river running at the base of the valley. That river was the Alatna, and it began at the continental divide north of the Arrigetch, and flowed through a beautiful valley as an easy class II river.

And this gave me a basic plan: use packrafts to float the Alatna River from its headwaters to Arrigetch Creek, and then hike up to the Arrigetch Peaks to see the granite mountains.

And this gave me a basic plan: use packrafts to float the Alatna River from its headwaters to Arrigetch Creek, and then hike up to the Arrigetch Peaks to see the granite mountains.

The next obstacle was figuring out how to get to this remote part of the world. To get there, we would drive from Huntsville to Nashville, fly from Nashville to Fairbanks, stay overnight in Fairbanks and then catch a one-hour flight to the tiny town of Bettles on a small prop plane. It was necessary to fly to Bettles because there are no roads to the small village. From Bettles, we would take a very small float plane for nearly two hours into the middle of the Brooks Range, where we would land on the headwater lake of the Alatna River at the Continental Divide. And if that weren’t enough adventure, once we were dropped off, we would spend 14 days paddling, camping, backpacking, and falling in love with the Brooks Range.

After spending months of acquiring more gear, training on the packrafts on local rivers, recruiting other people to go with us, planning two weeks worth of food, arranging all of the flights, packing backpacks, and day dreaming about the trip, we were ready to go. Tracy and I would be joined by Layne, a friend from Huntsville with whom I regularly go caving and canyoneering, and Mark, a friend I know through my brother who would meet us in Fairbanks from his home in Maryland.

After spending months of acquiring more gear, training on the packrafts on local rivers, recruiting other people to go with us, planning two weeks worth of food, arranging all of the flights, packing backpacks, and day dreaming about the trip, we were ready to go. Tracy and I would be joined by Layne, a friend from Huntsville with whom I regularly go caving and canyoneering, and Mark, a friend I know through my brother who would meet us in Fairbanks from his home in Maryland.

Layne, Tracy, and I finally left for Nashville after work on July 20, 2017.

We arrived in Fairbanks on July 21st, with almost no drama from the flights, and settled into a hotel room for the night. Mark arrived late that night, and on the morning of July 22nd, the four of us met at Wright Air Service to head to Bettles.

Bettles is tiny…really tiny. The nicest building in the community is the Ranger Station for Gates of the Arctic National Park. There are only a few other buildings, including one restaurant and two small lodges. The restaurant generally serves one meal at each meal time…the menu is just that one meal. The meals were good, though…and expensive. The arrival at Bettles was also a little hectic. We planned to drop a food cache at Circle Lake near the mouth of Arrigetch Creek, which meant we had to borrow bear canisters from the Park Service, repack our food for the cache into the canisters, and transform our flying luggage into our backcountry backpacks. We also tried to do all of this quickly so that we could fly out as soon as possible. Brooks Range Aviation, our charter for getting into the wilderness, does not have schedules…they just fly people out when they arrive. Unfortunately, a group had arrived before us and was slow to get ready to leave. As a result, we were able to get lunch, wander around Bettles, and relax for several hours before we were finally able to leave.

But, eventually, we loaded into an old pick-up truck and were driven a few miles out to a lake. After a few minutes, three float planes landed at the lake, and we loaded up into one of them.

And we were off.

Day One

The flight into Brooks Range was incredible. It took nearly two hours to fly to the top of the Alatna and the views were outstanding. In fact, Tracy expressed her nervousness about the trip when she said, “I would have been happy if we had just taken the flight and then turned around and gone back.” They will take you on a flightseeing trip, but we had bigger plans. And by 6 pm we were finally standing on the shore of Gaedeke Lake, with our packs stuffed full of food, camping gear, and packrafting gear.

The flight into Brooks Range was incredible. It took nearly two hours to fly to the top of the Alatna and the views were outstanding. In fact, Tracy expressed her nervousness about the trip when she said, “I would have been happy if we had just taken the flight and then turned around and gone back.” They will take you on a flightseeing trip, but we had bigger plans. And by 6 pm we were finally standing on the shore of Gaedeke Lake, with our packs stuffed full of food, camping gear, and packrafting gear.

The view at the Divide was amazing. Gaedeke Lake stretched into the distance as green-draped mountains rose above us. The sound of the float plane taking off and leaving us for 14 days deep in the Alaskan wilderness was one of the best feelings imaginable. It was liberating and intimidating and rewarding and demanding…it was great.

And now it was time to step into the wilderness.

Information about this trip is very scarce. The entire Park only sees about 10,000 visitors every year, and only a small portion of those float the Alatna and hike the Arrigetch. By comparison, The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which has 522,000 acres versus the 8.4 million acres of Gates of the Arctic National Park, receives over 11 million visitors every year. Let that sink in: 10,000 visitors for 8.4 million acres versus 11 million visitors for 522,000 acres. Because of these low visitation rates, it was very hard to find information about the route we planned to take. There was such a dearth of information, that I had to watch YouTube videos in foreign languages and read trip reports from decades earlier.

As I tried to plan the trip, I wished that I could find more details. I read something that said you had to hike about 4 miles until the Alatna had enough water to float. I read that the Alatna was an easy Class I river except for a Class II or III rapid that would likely need to be portaged near Ram Creek. I read something else that insisted the Alatna was actually a Class II or Class III river except for a Class IV rapid near Ram Creek. I read that the hike up to the Arrigetch was a nearly impenetrable tangle of alder bushes, but it’s easier if you go high. But I didn’t know exactly where the water levels would rise enough to be able to float, and I didn’t know how hard the rapids would be, and I didn’t know if there were strainers on the river, and I didn’t know exactly where the rapids were near Ram Creek, and I didn’t know where I was supposed to go high to avoid the alder bushes at Arrigetch Creek…I didn’t even know exactly which lake was Circle Lake, where our food cache would be located, because it wasn’t labeled on the map.

And now that I know the answers to these and many other questions, I’ve struggled with how much to include in this trip report. On the one hand, I wanted to know the answers before I left, and it was a little stressful not knowing. But on the other hand, it was more exciting…or more natural…or more challenging…or more rewarding to figure it out on our own. And since this was supposed to be an old-school epic Alaskan wilderness adventure, I think it was better that I didn’t know all of the answers before I left. So here’s how I’m going to leave many of those answers for this report: I’m not going to give any spoilers. It’s better to have some anxiety. It’s better to explore. It’s better to venture into the unknown. So, I’m not going to spoil the fun. But if you absolutely feel like you must know all of the minute details, email me and we can talk about it. But I urge restraint…it really is more fun to experience it with limited information.

So, based on what I knew, the plan was to hike about four miles until we could get enough water on the Alatna to float it. We planned to do that on Saturday and then start paddling on Sunday. But with our late start and the ground conditions, we only made it one mile in almost two hours of walking, and it was 8 pm. So we decided to find a campsite for the night and see how it went the next day.

So, based on what I knew, the plan was to hike about four miles until we could get enough water on the Alatna to float it. We planned to do that on Saturday and then start paddling on Sunday. But with our late start and the ground conditions, we only made it one mile in almost two hours of walking, and it was 8 pm. So we decided to find a campsite for the night and see how it went the next day.

The mosquitoes were pretty bad at the Divide, and we debated whether to camp by the river where it was sheltered, or to camp up higher where the wind would keep the bugs under control. We ultimately decided to camp up high. The wind did keep the mosquitoes at bay, but we found the ground too wet and spongy for our non-freestanding Tarptent. But we managed to get the stakes to stay in the ground after some creative arranging, and then we settled in for the night. Unfortunately, almost as soon as we crawled into our tents around 11 pm, a storm blew in, bringing with it 40 MPH winds that quickly overwhelmed the tenuous hold our tent stakes had in the tundra, and our tent collapsed.

This was a minor emergency, but after nearly 30 minutes of trying to solve the problem, I finally managed to turn the tent into the wind and tie the important tent lines to heavy backpacks. Problem solved and the rest of the night passed uneventfully as the strong winds lashed our tents.

Day Two

We awoke on Sunday to a storm. We immediately knew that the plan was already being challenged by Alaska. Based on our slow 1/2 mile an hour pace the day before, we knew that it would be tough to make it to the deeper water that day with enough time to get on the water and paddle. And we knew that if the weather stayed as bad as it was, then we wouldn’t want to be on the water, anyway. But we started hiking in that direction. The hiking was again very slow, and about 1/2 mile from our destination, we found a wonderfully sheltered campsite. It was still pretty early in the day, but the weather was nasty, the winds were howling, and we knew that we couldn’t paddle that day and we would probably not find a better campsite by continuing forward. So we stopped and set up camp. Layne and I took a hike to the place we planned to put-in just to see how deep the water was. We got a decent look at it through the alders and decided it would be fine. We then returned to camp and spent most of the day inside the tents to escape the weather.

We awoke on Sunday to a storm. We immediately knew that the plan was already being challenged by Alaska. Based on our slow 1/2 mile an hour pace the day before, we knew that it would be tough to make it to the deeper water that day with enough time to get on the water and paddle. And we knew that if the weather stayed as bad as it was, then we wouldn’t want to be on the water, anyway. But we started hiking in that direction. The hiking was again very slow, and about 1/2 mile from our destination, we found a wonderfully sheltered campsite. It was still pretty early in the day, but the weather was nasty, the winds were howling, and we knew that we couldn’t paddle that day and we would probably not find a better campsite by continuing forward. So we stopped and set up camp. Layne and I took a hike to the place we planned to put-in just to see how deep the water was. We got a decent look at it through the alders and decided it would be fine. We then returned to camp and spent most of the day inside the tents to escape the weather.

Day Three

The weather wasn’t much better when we awoke on day three. The forecast we received on my inReach satellite communicator said the weather would improve a little later in the day, so we spent a few hours in the morning waiting for the weather to get better. Eventually, the wind died down, so we headed to the river. After half a mile of hiking, we finally unpacked and inflated the packrafts, assembled the paddles, donned the PFDs, strapped the packs down to the rafts, and headed out onto the river. It finally felt like we were on an adventure…it finally felt like we were moving. We had 50 miles to go to reach Arrigetch Creek, and we were ready to get started. But 50 miles seemed pretty intimidating as we started heading south into the wilderness. As we started paddling, I felt the full weight of the realization that there was almost no way to get home now without traveling the full 50 miles down the river. That realization was both scary and exhilarating. This was the point of the whole trip.

The weather wasn’t much better when we awoke on day three. The forecast we received on my inReach satellite communicator said the weather would improve a little later in the day, so we spent a few hours in the morning waiting for the weather to get better. Eventually, the wind died down, so we headed to the river. After half a mile of hiking, we finally unpacked and inflated the packrafts, assembled the paddles, donned the PFDs, strapped the packs down to the rafts, and headed out onto the river. It finally felt like we were on an adventure…it finally felt like we were moving. We had 50 miles to go to reach Arrigetch Creek, and we were ready to get started. But 50 miles seemed pretty intimidating as we started heading south into the wilderness. As we started paddling, I felt the full weight of the realization that there was almost no way to get home now without traveling the full 50 miles down the river. That realization was both scary and exhilarating. This was the point of the whole trip.

But our going was slow. Much of this day was spent dragging the boats because there simply wasn’t enough water to float. Tracy and I were wearing drypants with integrated socks, so we didn’t mind the dragging. Mark and Layne were a little cold from all of the dragging, though. I had planned to do about 10 miles this day, but due to the late start and low water levels, we only made it about 7 miles. I was beginning to get worried that I had seriously over-estimated the distance we could travel each day.

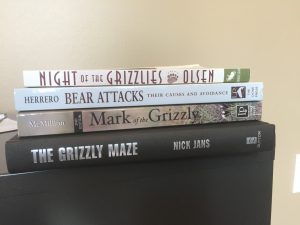

It should also be noted that every time we stopped the boats we saw bear tracks and moose tracks. We still hadn’t seen any wildlife, but their tracks were everywhere. We even saw what I believe was a cat track that belonged to a lynx. That was cool. Some of the bear tracks were quite large, and we were staying alert to grizzlies around the river. We had two cans of bear spray between us, Mark carried my Glock .40, and I was carrying a .454 Casull on my chest. I truly never expected to need the gun, but I figured we would sleep better knowing it was there.

It should also be noted that every time we stopped the boats we saw bear tracks and moose tracks. We still hadn’t seen any wildlife, but their tracks were everywhere. We even saw what I believe was a cat track that belonged to a lynx. That was cool. Some of the bear tracks were quite large, and we were staying alert to grizzlies around the river. We had two cans of bear spray between us, Mark carried my Glock .40, and I was carrying a .454 Casull on my chest. I truly never expected to need the gun, but I figured we would sleep better knowing it was there.

But we would soon get our first wildlife sighting. At one point, Mark and I saw Tracy stop and get out of her boat ahead of us. As we approached her, I wondered why she was out of the water and wondered if she had seen some wildlife. As we neared her, she and I both saw it at the same time: nearly half a mile away on the side of the mountain was a large grizzly foraging for berries. She hadn’t seen it when she stopped, but she saw it just as I saw it. Excited, Mark and I stopped to enjoy the sighting. Layne was ahead of us and didn’t know why we were stopped and wasn’t in a position to see up the mountain. While we were watching that bear, I looked further down river and saw movement on another mountain. Looking closer, I realized it was a second grizzly bear foraging for berries. This bear was further from us but closer to Layne. As we watched it, it started walking towards the river and disappeared into the brush. It was probably nearly half a mile from Layne, but we couldn’t see it anymore, it was headed towards him, and he didn’t know it was there. So we loaded back into the boats and paddled down to warn him. As we started paddling, the first bear started running down the mountain towards us. This gave me an adrenaline shot as I yelled to the others that he was running towards us as we scooted through shallow water. But he was still a long distance away, and he only ran a hundred yards or so before stopping and then ambling back up the mountain. I don’t know why he ran…I don’t think he was running at us…but he lost interest in it quickly.

We then got to Layne and told him to get back in his boat since there were two bears nearby and we had lost sight of one of them near him. We then continued down the river as we gushed about our first bear sighting. This was Mark’s first grizzly bear ever, and this was our first grizzly bear in the backcountry. It was exciting. And it was good that it had happened from so far away.

We later found a nice campsite on a gravel bar, with a cliff behind us, and settled in for the night.

Day Four

As we were getting dressed in our tents on the morning of day four, we heard something. We all stopped what we were doing to listen, and we soon heard the unmistakable sound of a lone wolf howl. It was exhilarating to hear the howl so far out in the remote wilderness. It sounded fairly far away and possibly on the other side of the river, so we went about our camp chores, and didn’t hear it again. A few minutes later, Mark was standing outside when he said he saw a wolf. I jumped out of the tent, trying to switch my camera lens, as Mark said the wolf was climbing the bank above our camp just a couple of hundred yards away. By the time I got my zoom lens on my camera, the wolf had reached the top of the bank and disappeared over the hill. But Mark was excited to have seen his first wolf.

After that excitement, we loaded up and got back on the river. Day four was radically different. The river that barely had enough water to float most of the time the day before was now running high, presumably from the rains of the previous days. The river that I expected to be a Class I paddle was most often a fast Class II with some Class II+ or even Class III sprinkled in periodically. We were surprised and a little nervous. We were making decent time now, at least, but soon we dropped into trees along the bank. Soon after entering the trees, Layne and I were in front and rounded a bend in the river to see a strainer (a tree hanging low over the river) on the left side with fast rapids flowing through it. We were able to paddle around the tree without any problems, but we pulled off once we got through it to make sure Mark and Tracy didn’t have any problems. When I looked back, I saw Tracy dragging her boat and looked back at Layne and commented that she was dragging her boat around the obstacle and she would be fine. I turned back to look at her, and I saw Mark frantically waving his paddle. I knew something was wrong, so I jumped out of my boat, pulled it up on the bank, and turned around to see Tracy’s boat come around the corner upside down.

In the frenzy of the moment, I didn’t see Tracy so I assumed she had accidentally let go of her boat while trying to drag it. So I swam into the fast, deep current to save her boat and backpack from being swept down the river. When I reached her boat, I saw her paddle and remember thinking, “Why is her paddle here?” But I grabbed her paddle with one hand and her boat with the other and swam and pulled with all of my effort to get the boat to the opposite bank. As I tried to pull it across, the current swept the boat past me and towards the bank, as it did, I saw Tracy in the water just behind the boat. She hadn’t just let go of the boat as she was  walking, somehow she had flipped out of the boat and was in the water. As I would learn later, she had gotten back into the boat and the rapids had taken her into the strainer, and the boat flipped, dumping her into the cold arctic river. Luckily, as I swung the boat to the bank, it also swung her to the bank. I saw her stop at the gravel bank as I struggled to maintain my grip on the boat, and I shouted for someone to help me. I looked across the river and saw Mark coming across. I then looked back at Tracy and saw that she was still in the water. I was then worried that she was hurt so I shouted for Mark to help her. He pulled her out of the water and then helped me get her boat and backpack out of the water. Tracy was nearly in a panic, but as we checked her, we realized that besides being scared, wet, and cold, she was fine.

walking, somehow she had flipped out of the boat and was in the water. As I would learn later, she had gotten back into the boat and the rapids had taken her into the strainer, and the boat flipped, dumping her into the cold arctic river. Luckily, as I swung the boat to the bank, it also swung her to the bank. I saw her stop at the gravel bank as I struggled to maintain my grip on the boat, and I shouted for someone to help me. I looked across the river and saw Mark coming across. I then looked back at Tracy and saw that she was still in the water. I was then worried that she was hurt so I shouted for Mark to help her. He pulled her out of the water and then helped me get her boat and backpack out of the water. Tracy was nearly in a panic, but as we checked her, we realized that besides being scared, wet, and cold, she was fine.

The excitement was over.

We spent the next hour warming her up and getting our boats from the opposite shore over to us, and then we kept on moving down the river. But now we were much more aware of the risk of strainers and the ever-increasing rapids, and we slowed down as we spent lots of time scouting rapids and dragging our boats around dangerous sections or potential strainers.

But we still made it about 11 miles for the day, and found a decent campsite just a mile or two above the rapids I was fearing near Ram Creek. We built our first fire that night to dry out our clothes from the swim, and spent the evening talking about the drama of day four.

Day Five

Day five started with the anxiety of the rapids I had read about near Ram Creek. The river was running much faster than I expected, so I was afraid that the rapids could be pushing Class IV. And I didn’t know if they were above Ram Creek, at Ram Creek, or below Ram Creek. So we took it slow as we approached Ram Creek. We scouted and dragged past a few rapids that morning, and then reached a rapid just above Ram that wasn’t anything more significant than many of the other rapids we had seen. We got out for a bathroom break, and Tracy, Mark, and I lined past the rapid mostly just because we were already out of the boats. Then we continued on down the river, passing Ram Creek, and soon the Alatna changed dramatically and became a flat, easy Class I river. After about a mile past Ram, I told everyone that we had obviously already passed the rapid we had been fearing, and we didn’t even notice it. I’m still not sure which rapid was supposed to have been the bad one. We had been through so much Class II+ water over the past day and a half, that we didn’t see anything near Ram Creek that looked any worse.

Day five started with the anxiety of the rapids I had read about near Ram Creek. The river was running much faster than I expected, so I was afraid that the rapids could be pushing Class IV. And I didn’t know if they were above Ram Creek, at Ram Creek, or below Ram Creek. So we took it slow as we approached Ram Creek. We scouted and dragged past a few rapids that morning, and then reached a rapid just above Ram that wasn’t anything more significant than many of the other rapids we had seen. We got out for a bathroom break, and Tracy, Mark, and I lined past the rapid mostly just because we were already out of the boats. Then we continued on down the river, passing Ram Creek, and soon the Alatna changed dramatically and became a flat, easy Class I river. After about a mile past Ram, I told everyone that we had obviously already passed the rapid we had been fearing, and we didn’t even notice it. I’m still not sure which rapid was supposed to have been the bad one. We had been through so much Class II+ water over the past day and a half, that we didn’t see anything near Ram Creek that looked any worse.

Either way, now the paddling was more relaxing. There were occasional rapids, but nothing like what we had encountered further up the river.

The weather had been great this day, and we pulled into a pretty campsite and enjoyed the 24-hour sun for another “night.”

Day Six

This was going to be our last day on the river before starting the backpack. This was a relaxing, slow day, as the river continued to deepen and level out, becoming a more consistent class I river. We spent most of this day just lazily floating down the river as we mentally prepared for the start of the backpacking portion of the trip.

We paddled nearly 15 miles this day because we didn’t have to drag our boats anymore. But the river was slow and the valley was wide, so we began to reconsider our plan. We were supposed to paddle down to Takahula Lake for our pick-up once we returned from the hike up to the Arrigetch. But since the water had slowed down so much, we weren’t sure we wanted to spend another day and a half paddling down the slow river. We were leaning towards spending extra time up in the Arrigetch and using my inReach to change our pick-up location to Circle Lake. But we decided to hold off on making a decision until later in the trip.

We paddled nearly 15 miles this day because we didn’t have to drag our boats anymore. But the river was slow and the valley was wide, so we began to reconsider our plan. We were supposed to paddle down to Takahula Lake for our pick-up once we returned from the hike up to the Arrigetch. But since the water had slowed down so much, we weren’t sure we wanted to spend another day and a half paddling down the slow river. We were leaning towards spending extra time up in the Arrigetch and using my inReach to change our pick-up location to Circle Lake. But we decided to hold off on making a decision until later in the trip.

As evening arrived, we needed to make a decision about where to camp. We needed to hike to Circle Lake in order to retrieve our food cache. The pilot had not landed at Circle on the way in to drop our cache, but he promised he would have it dropped before we needed it. He showed me on my map where he would put the cache, but we didn’t know if it had actually been dropped or exactly where it was. We also didn’t know the best way to get there since there are no trails and the terrain is unforgiving.

Looking at the map, I decided to stop right at the confluence of Arrigetch Creek and the Alatna River on the north side of the confluence. The reason I decided to do this was because the Alatna curved eastward away from Circle Lake just past the confluence, which would take us further away from the lake for a couple of miles. And then once it curved back towards the lake, I was worried there wouldn’t be any good campsites because the banks were becoming more forested and steeper. Additionally, it looked like it was going to be about a one mile hike coming in to Circle Lake from the north as well as from the south. So, I figured that we might as well save the paddling time and just hike from the north the next morning. So, we stopped and made camp for the night.

Day Seven

We got up this morning and packed up all of our packrafting gear and strapped everything to the backpacks for the hike to Circle. We needed to cross the Arrigetch immediately, but the water was slow and only about knee deep, so we didn’t have any problems with the crossing. We then headed straight towards Circle. The next two and half hours were miserable. The ground was covered in swamps, tussocks, and alders, and the air was filled with mosquitoes. It took over two hours to walk the one mile to Circle Lake. It’s hard to understand how tough it is to walk on tussocks until you’ve done it. The best analogy I’ve come up with is that it’s like walking on a large mushroom: it looks nice and large on top, but when you step on it, it can’t hold your weight and it flips you off. Walking on tussock is a sprained or broken ankle waiting to happen. It’s safer just to walk in the water around the tussocks, but that’s not easy, either, since the tussocks are often very close together.

On the way, we went through a small stand of trees about 30 minutes northwest of Circle, which seemed nice with some good campsites. And then we made it to Circle and navigated straight to our cache, which was thankfully waiting for us. We then spent the next two hours eating lunch and repacking food and trash. We also packaged up our packrafting gear and hung it in a tree. We wouldn’t need it for the trip up to the Arrigetch and we didn’t want to carry it up the mountain. It wasn’t easy finding trees that would hold the gear, but we managed to make it work.

On the way, we went through a small stand of trees about 30 minutes northwest of Circle, which seemed nice with some good campsites. And then we made it to Circle and navigated straight to our cache, which was thankfully waiting for us. We then spent the next two hours eating lunch and repacking food and trash. We also packaged up our packrafting gear and hung it in a tree. We wouldn’t need it for the trip up to the Arrigetch and we didn’t want to carry it up the mountain. It wasn’t easy finding trees that would hold the gear, but we managed to make it work.

After these chores were done, we started towards Arrigetch Creek. Like so many other things on this trip, we had very little information and didn’t know exactly where to go. There were no trails, so we climbed a little way up the mountain and then turned northwest and went straight towards Arrigetch Creek.

This hike was pretty awful. The tussocks were everywhere, we had already had a rough day getting to Circle, and we were moving terribly slowly. It was just a little over 2 miles to Arrigetch Creek, and it took us more than 4 hours. It rained much of the day, adding to the unpleasantness. By the time we reached the Arrigetch, we were exhausted and ready to call it a day. Luckily, we quickly found a good campsite, so we made camp by the creek and passed out for the “night.”

Day Eight

Today we hoped to find some semblance of a trail to get us to the peaks. If we didn’t, this was going to be pretty awful. Luckily, we were able to find a “trail” that headed up alongside the creek. The trail would barely be considered a game trail in any other national park, but here it felt like a superhighway compared to what we had done the day before. But the trail was still completely blocked by alders, and Tracy described it as “full-contact hiking,” as we were getting beaten up by the alders every step of the way. But, it was still much easier than the day before.

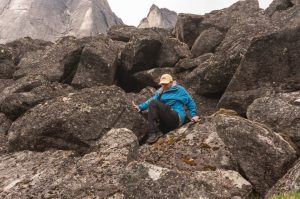

At least it was until we hit a boulder field.

This is another one of those places where I hesitate to spoil the backcountry experience with what we learned, so I’ll leave it as this: we didn’t have to hike through the boulder field.

But we didn’t know that, so we hiked through the boulder field, and attempted to find the great “trail” on the other side. We took over an hour to find any semblance of a trail, but eventually we found the trail we had lost over an hour earlier. That hour was terribly demoralizing because we had been so happy to have a route to follow. But when we found the route again, our spirits rose and we pressed forward.

But we didn’t know that, so we hiked through the boulder field, and attempted to find the great “trail” on the other side. We took over an hour to find any semblance of a trail, but eventually we found the trail we had lost over an hour earlier. That hour was terribly demoralizing because we had been so happy to have a route to follow. But when we found the route again, our spirits rose and we pressed forward.

Due to the diversion, though, we made slow time up the creek, so we decided to stop for the night on the way up. The decision was easy once we found an idyllic, beautiful campsite on an island in the middle of the Arrigetch. This island was formed by a very shallow rivulet that broke around the island, forming a small waterfall and a beautiful, green pool. We didn’t even get our boots wet crossing the rivulet, and the island had great tent sites. We also had a great view up the main channel of the river on the opposite side of the island towards the Arrigetch Peaks. This really was a great site. So, we settled in, ready to make it to the Peaks the next day.

Day Nine

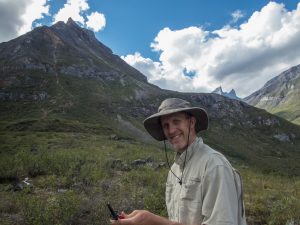

We got up this morning and continued up the valley. The views got better and better the closer we got. The granite spires rose majestically out of the valley, looking like nothing else we had seen in the Brooks Range. It was easy to see how most of these remote peaks didn’t see their first ascents until the 1970s…and the majesty of the mountains explained why these summits beckoned the likes of Jon Krakauer and other notable rock climbers for the first ascents.

We got up this morning and continued up the valley. The views got better and better the closer we got. The granite spires rose majestically out of the valley, looking like nothing else we had seen in the Brooks Range. It was easy to see how most of these remote peaks didn’t see their first ascents until the 1970s…and the majesty of the mountains explained why these summits beckoned the likes of Jon Krakauer and other notable rock climbers for the first ascents.

But for our modest trip, I was planning to camp at the confluence of two streams at the top of the valley, and then spend the next couple of days exploring the head of the two cirques.

Just before we reached the confluence of the streams, we met the first person we had seen in nine days. It turned out that she was a world-class rock climber who had been climbing one of the peaks. She was from Barcelona, trekking solo, and had been on her trip for 40 days. She had summited Xanadu after spending 17 days on the wall, and she made us all feel like losers since we weren’t doing anything nearly as hard as she was doing. She assured us that we would see her more because she had to make five trips of about 3 hours each in order to carry all of her gear down the mountain in stages…it was going to take her 12 more days just to make the 12 mile hike back to Circle Lake.

She told us that she had only had one bad encounter with a bear. Her encounter was on the first night of her nearly 60-day trip and had occurred with a black bear in the woods we had hiked through near Circle Lake. She had also seen a grizzly near where we were talking, but that had been a month earlier. We congratulated her on her climb and continued up the trail.

I was surprised that the climber had seen a bear this far up the valley, because I hadn’t seen any bear signs at all since we had left the Alatna. It was also hard for me to imagine a bear coming through the thick alders to get up this valley.

We went about 5 minutes after talking to the climber and started looking for a campsite. I was in the back of the line, looking up the hill at a spot that I thought might be a good campsite, when I noticed movement right in the middle of the site, and realized there was a large grizzly bear just about 40 yards up the hill from us. I stopped, whispered for the others to come back to me, while I pulled out my camera. This was officially the closest I had ever been to a grizzly, and it was beautiful.

We went about 5 minutes after talking to the climber and started looking for a campsite. I was in the back of the line, looking up the hill at a spot that I thought might be a good campsite, when I noticed movement right in the middle of the site, and realized there was a large grizzly bear just about 40 yards up the hill from us. I stopped, whispered for the others to come back to me, while I pulled out my camera. This was officially the closest I had ever been to a grizzly, and it was beautiful.

The others moved back to me like the Scooby Doo gang going into a haunted house: they bunched up, took one step, and tried to see through the bushes. I kept trying to urge them on, and they finally got back to me after I pointed at the ground at my feet and whispered, “Stand here!”

The bear was foraging for soap berries, and paid absolutely no attention to us whatsoever. I find it hard to believe he (or she) didn’t know we were there, but he didn’t look at us or move towards us at all. But we didn’t want to push our luck, so after taking a couple of pictures, we quickly moved on down the trail.

We were a little spooked now since there was a large bear behind us and uphill from us that we couldn’t see anymore. We quickly arrived at the confluence of the streams and hurried across to put some distance between us and the bear. We obviously didn’t want to camp anywhere near the bear, so we crossed the creek coming out of the Aquarius Valley, and then headed up the ridge to the head of the cirque. We hiked a mile and a half or so, and found a great campsite just below the moraine wall near the top of the cirque. I was confident that there were no berries near us and I didn’t believe the bear would come this far up the valley. So we made camp at one of the most beautiful sites I have ever found. The granite spires of the Arrigetch rose like fingers above our camp, as the stream flowed out of the cirque into the lush green grasses of the valley. It was a great site, where we could also see all the way down the valley, back over the Alatna River, to the mountains east of the Alatna.

Mark and Layne did a little hiking up one side of the cirque, while Tracy and I relaxed in camp before we all called it a night.

Day Ten

The weather forecast I received on the inReach this morning was calling for deteriorating weather later in the day, including strong winds. I didn’t particularly want to be stuck above tree line with another nasty wind storm blowing in, so I suggested that we spend the morning hiking around the cirque and then hike back down to the island campsite. Everyone agreed with this, so Tracy and I went up to the top of the moraine wall where Layne and Mark had gone the day before, and Mark and Layne took the right fork of the Aquarius Valley. The view at the top of the cirque was magical. Just being in a glacial cirque, surrounded by granite spires, while realizing we were seeing a place that very few people would ever see, was awe inspiring. This is an expedition rock-climber’s mecca, but there were no other people and the only sounds that graced the majestic views were the bubbling of the creek and the wind blowing through the rocks. The effort it took to get here…the money…the planning…the risks…everything that went into standing on this spot at the top of the cirque in the Arrigetch Peaks was worth it all as we stood there alone and looked over these granite fingers and the valley that stretched out below them.

The weather forecast I received on the inReach this morning was calling for deteriorating weather later in the day, including strong winds. I didn’t particularly want to be stuck above tree line with another nasty wind storm blowing in, so I suggested that we spend the morning hiking around the cirque and then hike back down to the island campsite. Everyone agreed with this, so Tracy and I went up to the top of the moraine wall where Layne and Mark had gone the day before, and Mark and Layne took the right fork of the Aquarius Valley. The view at the top of the cirque was magical. Just being in a glacial cirque, surrounded by granite spires, while realizing we were seeing a place that very few people would ever see, was awe inspiring. This is an expedition rock-climber’s mecca, but there were no other people and the only sounds that graced the majestic views were the bubbling of the creek and the wind blowing through the rocks. The effort it took to get here…the money…the planning…the risks…everything that went into standing on this spot at the top of the cirque in the Arrigetch Peaks was worth it all as we stood there alone and looked over these granite fingers and the valley that stretched out below them.

But the weather was changing, and we needed to get back to camp to meet Layne and Mark, so we headed back down. We arrived before they returned, so we decided to go ahead and eat lunch. While eating, we saw a group of four people hiking down the mountain from the direction Mark and Layne had gone. We soon saw Mark and Layne coming down, also. They told us that the  group was from Switzerland and had flown in from Coldfoot and been dropped off by a wheeled plane on a gravel bar on the Alatna, thereby bypassing Circle Lake. They were out for a few days, as part of a long trip around Alaska. We talked about how unusual it was that we had only seen two groups and they were both from foreign countries.

group was from Switzerland and had flown in from Coldfoot and been dropped off by a wheeled plane on a gravel bar on the Alatna, thereby bypassing Circle Lake. They were out for a few days, as part of a long trip around Alaska. We talked about how unusual it was that we had only seen two groups and they were both from foreign countries.

After finishing lunch, we packed up and started down the mountain. Mark wondered if it would be safe to camp on the island if it rained too much, but I dismissed the concern since the rivulet had been so shallow. If this were a novel, this would be called foreshadowing. On the way down, we saw another grizzly bear a few hundred yards away. It may have been the same bear from the day before, but we couldn’t be sure. We continued down the mountain and made our way to the island and set up camp. We ate dinner and left our food on the mainland, 100 yards from camp, on the other side of the rivulet. After dinner, it started raining pretty hard, so we crawled into the tents for the night.

About 11 pm, I looked out at the rivulet and wondered if it looked like it was rising. Not wanting to disturb the others, though, I ignored the concern and went to sleep. If this were a novel, this would be called foreshadowing.

Day Eleven

I woke up at 7 am on day eleven to the roar of water. Lots of water. I crawled out of the tent to an unnerving sight: the rivulet was a raging torrent of water, making it unsafe to try to get off the island. The main channel of the river was completely frightening because of how fast and swollen it had become. And the idyllic pool and the small waterfall on the rivulet side were gone, replaced by raging currents and water that had risen nearly two feet.

I woke up at 7 am on day eleven to the roar of water. Lots of water. I crawled out of the tent to an unnerving sight: the rivulet was a raging torrent of water, making it unsafe to try to get off the island. The main channel of the river was completely frightening because of how fast and swollen it had become. And the idyllic pool and the small waterfall on the rivulet side were gone, replaced by raging currents and water that had risen nearly two feet.

And our food was on the other side.

The forecast called for a 40% chance of rain during the day, and then something like a 70% chance of rain later in the evening. We spent an hour staring at the water, debating our options, and we ultimately decided just to wait and hope that the water level dropped before it started raining again.

We huddled in our tents, praying that the rain would hold off long enough for the water level to drop. Periodically, we climbed out of the tent, only to be demoralized by the raging waters. But all we could do was wait.

And the rain held off. By about 1:30 pm, the water level was obviously dropping. We began to think we might have a chance to make it across if the rain could hold off for another hour or so. Just before 2:30 pm, the clouds up the valley started to look heavy with rain. The water had dropped several inches, the flow had decreased significantly, and we could see some of the rocks that had lined the small pool. We knew those rocks formed a rim across the stream, and we believed we could pick our way across on those rocks with minimal risk. And with the skies looking iffy, we decided it was time to go. So we very quickly packed up camp, tied cords to Mark, and sent Mark across.

He made it across with no problem, with water barely getting above his knees. We then rigged a pull cord system to get Tracy’s hiking poles back across the river, and then Layne went across. I then pulled the poles back across, and the carabiner popped off the cord, and the hiking poles, the ones we needed to pitch our tent, fell into the river. Luckily, the carabiner didn’t pop off of the straps of the poles, and I was able to continue pulling them through the river with the pull cord. Tracy then crossed, I pulled the poles back, removed the cords, checked the campsite, and quickly scurried across the stream.

And the second big drama event of the trip was over.

We went straight to our food and ate the first meal of the day at about 4 pm. We then started down the mountain, hoping to get to the camp we had used after leaving Circle Lake on night seven. On the way down, we passed an American couple who were doing almost exactly the same trip we were doing. While talking to them, the Swiss group came down, and they said the night had not been enjoyable in the cirque while it was storming. It was strange that every person on the mountain except the solo climber had met in the same place at the same time after going so long without seeing anyone. But everyone out there was fun to talk to.

We went straight to our food and ate the first meal of the day at about 4 pm. We then started down the mountain, hoping to get to the camp we had used after leaving Circle Lake on night seven. On the way down, we passed an American couple who were doing almost exactly the same trip we were doing. While talking to them, the Swiss group came down, and they said the night had not been enjoyable in the cirque while it was storming. It was strange that every person on the mountain except the solo climber had met in the same place at the same time after going so long without seeing anyone. But everyone out there was fun to talk to.

We soon continued down the mountain, and we were able to avoid the boulder field that had stressed me out all day…I hadn’t been excited about trying to pick our way across the boulders while they were wet. And we soon made it to the base of the mountain and back to the campsite we had been at several days earlier.

When we had left this campsite previously, we had seen what looked like a big hawk. Upon returning, we saw it again, and realized there were two of them and there was a nest right above the campsite. We later learned from the Park Ranger that they were Gyrfalcons. Other falcons flew in while we were there, and there was some kind of fight, and we later saw a dead falcon hanging above the nest. It was a little bit of Wild Kingdom right above our tents.

Day Twelve

We decided the day before that we would have the time to make the paddle to Takahula Lake, but we really didn’t want to make the effort. The Arrigetch was still very swollen, and we knew that the Alatna would also be swollen. That would make the paddle to Takahula faster than we had worried it would be, but it could also make it more dangerous. So we tried, via the inReach, to arrange to be picked up at Circle Lake a day earlier than planned. However, the plane company said the weather had been too bad and they wouldn’t be able to make it a day early. So, we decided to leave the day we had originally planned to leave, but we changed the pick up location to Circle Lake.

So we spent day twelve just hanging out around camp. We didn’t move camp, so we just mostly relaxed. Mark, Layne, and I tried to scope out a better route towards Circle Lake than the route we had taken on the way in, and we believed we found a better route that started low, hopped between stands of trees, and then moved up the ridge, picking through game trails. While we were gone, Tracy cranked up music on her phone so she could dance around inside the tent and keep the bears away.

So we spent day twelve just hanging out around camp. We didn’t move camp, so we just mostly relaxed. Mark, Layne, and I tried to scope out a better route towards Circle Lake than the route we had taken on the way in, and we believed we found a better route that started low, hopped between stands of trees, and then moved up the ridge, picking through game trails. While we were gone, Tracy cranked up music on her phone so she could dance around inside the tent and keep the bears away.

We did see the solo climber again. She dropped a gear bag near our camp, so we spent a lot of time learning more about her and her background. Her story is fascinating.

She told us more about her encounter with the black bear early in her trip. The bear had harassed her all night, and tried to drag off some of her gear, ultimately destroying her water bladder. It turned out that the encounter had occurred in the campsite we intended to use the next night. So, that was nice to realize. But she soon needed to head back to the rest of her gear, so she returned up the trail.

The Swiss also came through, and they were supposed to be picked up the next day, but they had to cross the Arrigetch and they didn’t know if they would be able to cross it since the water was so high.

And we spent the rest of the day relaxing in camp.

Day Thirteen

This was a day we had been dreading. The hike from Circle Lake to this camp had been miserable, and now we had to do it again. This time, though, we took our time and picked out routes through stands of trees and via game trails that meandered in the area. Our route wasn’t direct, since we were piecing together game trails, and we weren’t able to avoid the tussocks entirely, but the hike was not nearly as bad as it had been on the way in, and we were happy to arrive at the camp in the woods early in the afternoon.

This was a day we had been dreading. The hike from Circle Lake to this camp had been miserable, and now we had to do it again. This time, though, we took our time and picked out routes through stands of trees and via game trails that meandered in the area. Our route wasn’t direct, since we were piecing together game trails, and we weren’t able to avoid the tussocks entirely, but the hike was not nearly as bad as it had been on the way in, and we were happy to arrive at the camp in the woods early in the afternoon.

We didn’t see any signs of the bear, and we had an uneventful evening in camp.

Day Fourteen

Brooks Range Aviation had told us to be ready for pick-up by 10 am. So we got up early and headed over to Circle Lake to wait for our ride out. The weather over us had been nice the day before, but the clouds had been low further down the valley, and we hadn’t seen or heard any planes at all for at least two days, so we were worried about getting picked up on time. We knew the Swiss were supposed to have been picked up the day before, but we hadn’t seen or heard any planes, so we knew the weather had been bad enough to keep planes grounded for several days. We were afraid that the planes were backed up and they wouldn’t be able to pick us up on time. Nonetheless, we got to Circle Lake a little after 9, where we retrieved our packrafting gear and ate breakfast while waiting for our flight.

About 10:15, Tracy was by the lake and she said people were paddling on the lake towards us. As they got closer, we realized they were three Park Rangers who had been floating the Alatna. They had told us before we left Bettles that they were going to do a patrol down the Alatna that week but we knew they were supposed to have returned to Bettles on Wednesday…it was Friday now. So, they had been stuck out there for two days past their scheduled pick-up date because of the weather. So now we were really worried about getting picked up on time. Just a few minutes later, we heard a plane and saw it land on the opposite end of the lake, then taxi towards us. But since the Park Rangers were overdue, we knew they would get first dibs…and they did. So we had to stand there and watch our plane take off without us.

About 10:15, Tracy was by the lake and she said people were paddling on the lake towards us. As they got closer, we realized they were three Park Rangers who had been floating the Alatna. They had told us before we left Bettles that they were going to do a patrol down the Alatna that week but we knew they were supposed to have returned to Bettles on Wednesday…it was Friday now. So, they had been stuck out there for two days past their scheduled pick-up date because of the weather. So now we were really worried about getting picked up on time. Just a few minutes later, we heard a plane and saw it land on the opposite end of the lake, then taxi towards us. But since the Park Rangers were overdue, we knew they would get first dibs…and they did. So we had to stand there and watch our plane take off without us.

And we waited.

Lunch came and went, and we waited.

Around 1:30 or so, we saw two floatplanes fly up the valley, and one of them was the plane that had picked up the rangers earlier in the day. We figured they were heading up to drop off some people and would pick us up on their way back.

About 2:00 or 2:30, a wheeled plane flew by and landed about a mile away, and we knew the plane for the Swiss had finally arrived.

About 2:00 or 2:30, a wheeled plane flew by and landed about a mile away, and we knew the plane for the Swiss had finally arrived.

About 3 pm, the wheeled plane took off, and one of the float planes came flying directly overhead. It was the one that had landed earlier, but he didn’t show any signs of landing this time. As we were watching the two planes fly down the valley, Tracy said, “Um, there’s another plane.” We turned around, and the other float plane we had seen earlier had snuck up on us and was landing just a few yards away on the lake.

Our ride had arrived and our 14 day trip had come to an end.

We loaded up and made the over one hour flight back to Bettles.

Final Thoughts

Even though Bettles doesn’t have any more than 50 people, it still felt like culture shock to arrive back to “civilization.” After 14 days in the most remote wilderness I could have ever imagined, it was startling to see signs of humans again.

But I wanted a shower and a real meal, so I was willing to make the transition.

But I wanted to stay out there. We have been in the most remote wilderness areas in the lower 48, and I have been enamored by all of them. But this was different. This was a wilderness that made me feel like a tiny dot on a large planet. This was a wilderness that made me feel insignificant. I felt like I had been swallowed by this wilderness for 2 weeks and then plucked out of it by a tiny fly that returned me to the world of humans.

This wilderness made me want to disappear in the mountains more than any other wilderness has ever done.

It’s hard to explain this trip, and I’ve been trying to describe it to friends and family for three weeks. How do you summarize vast tundra stretching over the Arctic Divide, rain swollen rivers sweeping you down through the Arctic for fifty miles, the thrill of seeing grizzly bears in the wild with one of them less than 50 yards away, the rush of hearing a wolf howl early in the morning, the fear when you turn around and see your wife’s boat flying wildly through a rapid without her in it, not seeing darkness for over two weeks as the sun never really sets, hiking for miles through a tangle of trail-less alders to finally see the majesty of a granite encircled cirque, not seeing another single human being for nine straight days and only seeing seven people in 14 days, meeting a world-class climber doing her thing in a world-class climbing environment, going to sleep on an idyllic island in the middle of a creek and waking to the realization that the overnight rains turned the small stream into a raging torrent and now you’re stranded on the island, being surrounded by roadless wilderness that is so large it’s hard to grasp, imagining how small you really are in such an expansive wild country, realizing that small mistakes can be big problems when the closest human civilization is hours away by airplane, thinking about where you are on the planet and understanding just how far north and how remote you really are, etc, etc? I can’t do it…I can’t summarize it. The summary of this trip will either have to be a book or one word: epic.

It’s hard to explain this trip, and I’ve been trying to describe it to friends and family for three weeks. How do you summarize vast tundra stretching over the Arctic Divide, rain swollen rivers sweeping you down through the Arctic for fifty miles, the thrill of seeing grizzly bears in the wild with one of them less than 50 yards away, the rush of hearing a wolf howl early in the morning, the fear when you turn around and see your wife’s boat flying wildly through a rapid without her in it, not seeing darkness for over two weeks as the sun never really sets, hiking for miles through a tangle of trail-less alders to finally see the majesty of a granite encircled cirque, not seeing another single human being for nine straight days and only seeing seven people in 14 days, meeting a world-class climber doing her thing in a world-class climbing environment, going to sleep on an idyllic island in the middle of a creek and waking to the realization that the overnight rains turned the small stream into a raging torrent and now you’re stranded on the island, being surrounded by roadless wilderness that is so large it’s hard to grasp, imagining how small you really are in such an expansive wild country, realizing that small mistakes can be big problems when the closest human civilization is hours away by airplane, thinking about where you are on the planet and understanding just how far north and how remote you really are, etc, etc? I can’t do it…I can’t summarize it. The summary of this trip will either have to be a book or one word: epic.

It was epic. This trip made all of my past epic trips seem like training wheels for this trip. This made me want more epic trips…more real epic trips. This trip made me want more wilderness. This trip made me want more.

My first trip to Alaska around Seward did not hook me like I had expected. But this one did. This trip showed me what true wilderness is. This was a wilderness that showed me how the planet has looked for hundreds or thousands of years. This wilderness hooked me.

I hope no one ever reads this trip report and gets the same bug, and I hope no one else ever visits this vast, roadless, trail-less, unrelenting, unforgiving, dangerous, expensive National Park.

I want this place to stay hidden and unknown and quiet. This is wilderness the way it was meant to be.

[mapsmarker marker=”102″]

Fantastic write-up! We did basically the same trip just a few days ahead of you (7/14 to 7/24). I believe we stayed at the same Arrigetch Creek campsite you describe. You can read my account of our trip, just google: basecamp nikiski

Hey there!

Me and a friend just did this trip in June 2018. Your write-up was a lot of help in preparing for our own trip. We also got stuck on an island due to a storm, so that particular dilemma really spoke to me!

Thanks for taking the time to put your experience together for the rest of us to read. It definitely helps.

If you’re interested, I did the same thing after our trip. You can read all about it at https://aussiesonthealatna.com/

Thanks again!

Ryan

I’m super happy to hear that my trip report helped you on your trip. I enjoyed reading your report. It’s funny how much we slept each night, too. People kept asking us how we slept with 24-hour daylight…I’m like, “The problem was waking up with 24-hour daylight!” And it’s interesting that we both got stuck on islands from rising water. If you haven’t read Bob Marshall’s Alaska Wilderness: Exploring the Central Brooks Range, I highly recommend it…he also got stuck. And I’ll definitely be going back. That place was amazing, and I have my eye set on a Brooks Range traverse.

Just found myself a copy of that book. Thanks for the recommendation! Can’t wait to find out how Bob managed to get himself stuck too.

I don’t think I’ve ever slept better. You certainly earn your Z’s.

The hardest part about being stuck for us was deciding not to do anything and to wait it out. It’s a tough call when all you want to do is get out of what feels like a dangerous situation. But it worked out for both of us!

Looking forward to seeing something on your traverse in the future.

Starting to plan our trip for 2021 or 2022 (Depending on the COVID situation). Thanks for this it was super helpful.

I’m glad you found some useful information! It’s a great location, and I’m sure you’ll love it. I’m currently in the early stages of planning a month long traverse of the range in 2022, if I can find people to go with me!

Hi,

I read your report on Gate of the Arctic. Great work and greaet video! I am leading an adventure in June. We will be packrafting a section of the Alatna River and hiking in the Arrigetch Mountains. I was wondering if you found it necessary to wear a dry suit while packrafting. My friends and I will be using a large 125lbs boat.

Thanks!

Sam

I’m glad you enjoyed the trip report, and that is a great question. We did wear dry pants with integrated feet for the paddling portion. We also wore our rain jackets. Two of the people in or group wore regular rain pants instead of dry pants. Obviously, they didn’t die, but they were not nearly as comfortable as we were in our dry pants. There was a LOT of dragging the boats, so we spent a lot of time in the water. The dry pants, with warm layers on underneath, made that considerably more comfortable. You’ll be there earlier in the year than we were, so you may have more water, which will mean less dragging. Also remember that you’ll probably have to carry your gear at least 4 miles from the drop-off before there’s enough water to float. It’s a great trip! I’m sure you’ll love it!

Et vous êtes français. J’ai étudié le français à l’université!